Focusing on “Researchers’ Big Picture,” this series explores the future societies they envision through their work. How does their research intersect with our lives? Their visions might provide valuable insight into the path ahead for all of us.

Resource circulation is one of the key factors in achieving a sustainable society. We spoke with Maria, who shared her vision of the future, shaped by her unique perspective rooted in her familiarity with wood.

Interviewing:

・Name: Maria Larsson

・Affiliation: Project Research Associate, Department of Creative Informatics, Graduate School of Information Science and Technology, The University of Tokyo

Drawn to Japan by the Beauty of Timber Joinery

▶︎ You research wood, but why did you specifically focus on kigumi (timber joinery)?

My home country, Sweden, is mostly covered in forest and has a culture of using wood as a building material, similar to Japan. . Although joinery exists in Europe, just as in Japan, it does not have the same number of variations. Japanese kigumi has a history of master carpenters refining and developing appropriate designs through trial and error, selecting the best joint based on the applied load or assembly direction. This is very intriguing.

I believe the extensive development of kigumi in Japan is related to climatic characteristics—high heat and humidity unsuitable for metal—the need to maintain structural strength due to frequent earthquakes, and the cultural background of viewing “buildings as part of nature.”

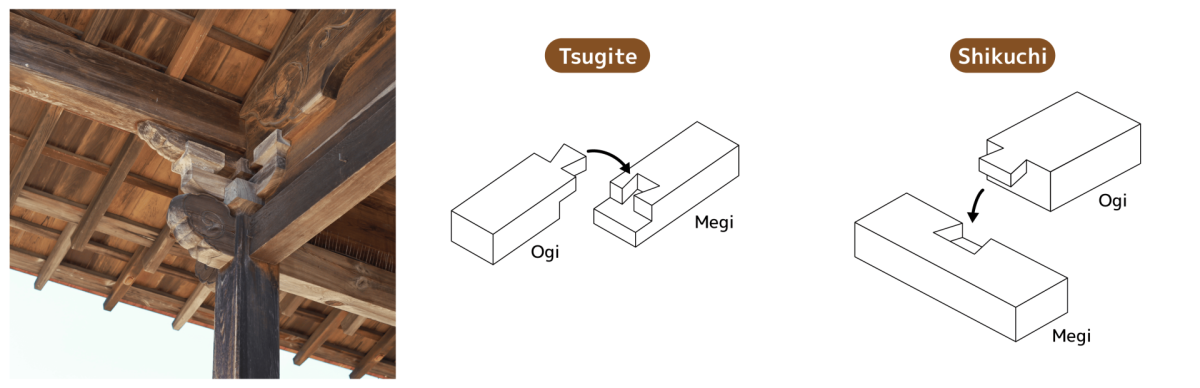

Kigumi is the technique of assembling wooden pieces together like a three-dimensional puzzle, without using nails or glue. (Picture: Itsukushima Jinja, Hiroshima, Japan)

The name for the joint varies depending on the direction the wood is assembled etc.,. but “The Tsugite” of this research encompasses different joint types.

▶︎ What kind of research are you working on Kigumi ?

I have a background in architectural design, Computer Graphics (CG), and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). Currently, I focus on Computational Design, which involves simulating the structure and function of buildings and furniture before they are designed. I felt that combining kigumi (traditional Japanese joinery) with computational design could generate many new ideas for utilizing wood and creating new designs, leading me to pursue various projects.

While wood research is now central, my ultimate goal is the realization of a Sustainable society through the effective utilization of limited global resources. For this purpose, the key are considering materials and designs that account for resource circulation, and reviewing manufacturing methods and processes by utilizing new technologies. We also developed Tsugite to enhance the value of wood, a sustainable material that is globally recognized.

Making Kigumi Accessible, Passing on the Tradition

▶︎ Could you tell me about Tsugite?

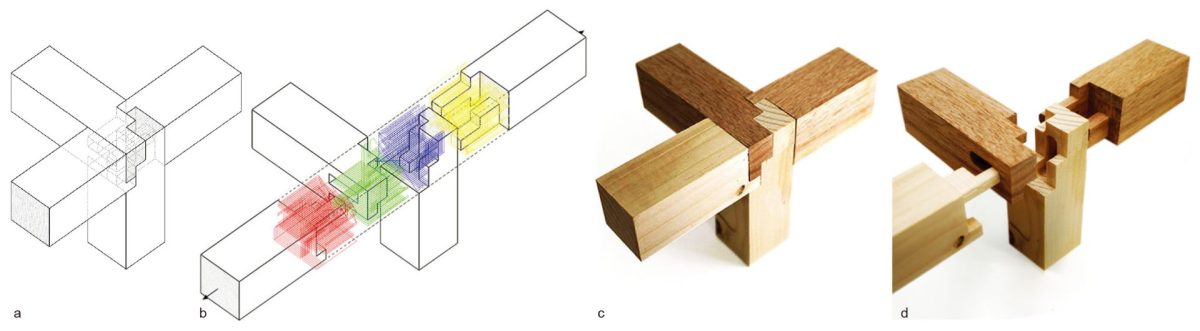

Kigumi involves combining a male piece (otogi) and a female piece (megi), which requires designing both pieces to fit perfectly. Tsugite is a software we developed to design Kigumi, which once you change the shape of one part (otogi or megi) on the computer, the other part automatically adjusts its geometry. This allows anyone to easily create the model. If there is a weak part in the geometry of a joint part, the system displays an error, making it applicable to real-world product design.

By inputting the designed data, the CNC machine will automatically process the wood. Kigumi, which traditionally required immense time and cost for design and processing, can now be handled smoothly on a computer.

▶︎ You could probably use 3D printers to create joinery from materials other than wood, which would broaden the possibilities for kigumi. What are your thoughts on that?

While 3D printers have the advantage of being able to produce complex shapes, they require the same amount of material as the resulting component, and certain materials can have a high environmental impact. Although wood-based materials are now available, they often contain glue and are not 100% wood-derived. Since I am pursuing research with the goal of realizing a sustainable society, I want to be cautious about applying this technology to non-wood materials.

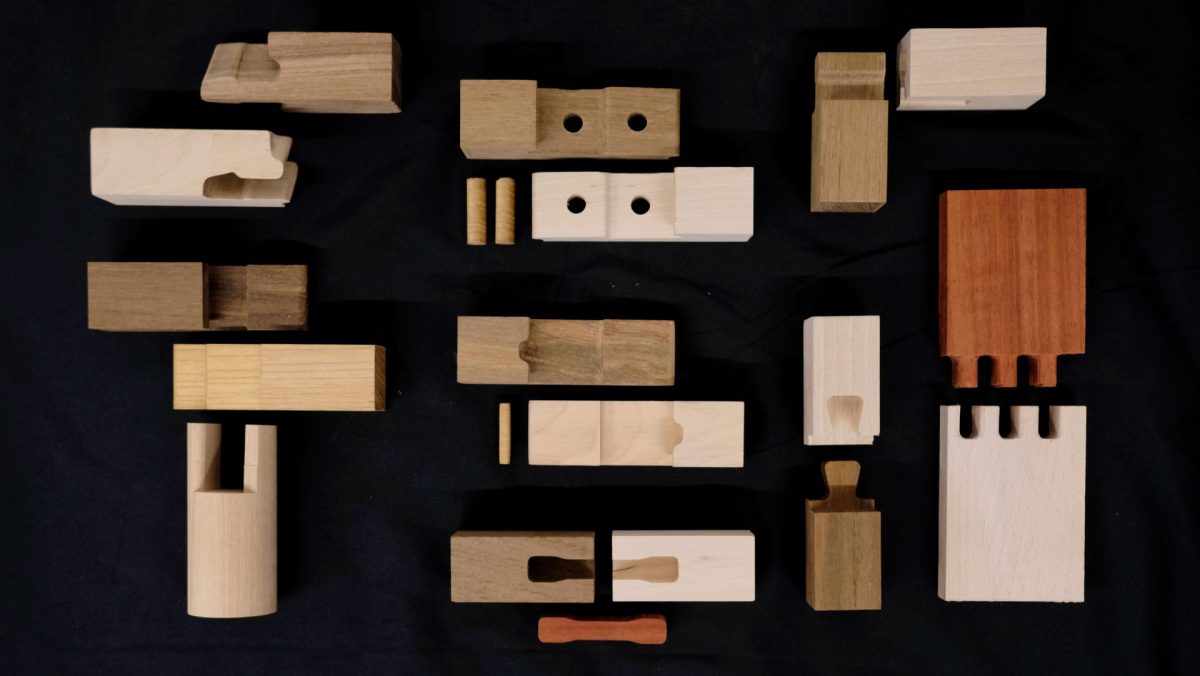

Here is a miniature model I made with Tsugite.

▶︎ Wouldn’t it be interesting if you make children’s puzzle or educational toy? They can learn the design of kigumi and it’s fun just to assemble and disassemble too.

Yes. While that is good, we first intend to expand Kigumi (traditional timber joinery) into re-assembly furniture. Although self-assembly furniture is already widespread, most products use non-wood materials such as metal bolts to secure the parts together. Kigumi furniture requires no bolts, nuts, or tools, and since it uses no mixed materials, it also has the advantage of being easy to recycle.

▶︎ That’s fascinating. If the parts can become products in their own right, they would fit well with platforms like Mercari.

Mercari is a circular platform where people sell unwanted items and those in need buy them. This aligns perfectly with my theme: “What is the best way to manufacture products so they can be used longer?”

For example, when furniture breaks, replacing it is costly, and we don’t want to easily discard items we have long cherished. With kigumi furniture, you can buy only the broken parts and continue using the item while repairing it. As history is etched into the furniture this way, its history itself gains value, allowing it to maintain high market value, similar to antique furniture.

Since kigumi furniture can be easily disassembled and the parts circulated as individual items, I believe it would lead to active trade on platforms like Mercari – between those wanting to fix beloved furniture and those selling spare parts they no longer need.

▶︎ We will also need the next generation to inherit Kigumi technology however, there is a problem with a lack of successors. Do you have any thoughts on this point?

Kigumi shapes are complex, making design or the process itself difficult. Creating them has historically required the skilled knowledge and experience of a master artisan. This knowledge was seemingly passed down through “learning by observation” however, that method requires time for mastery.

However, if computer utilization allows for shortened learning times, the number of people exposed to kigumi and the opportunities to engage with it will increase, facilitating talent discovery and development.

Since Tsugite features a user interface that is easy for anyone to use, the number of people capable of working with kigumi will likely grow. As awareness spreads, existing kigumi techniques will be re-appreciated, and the potential for new kigumi ideas to emerge will also increase, we believe.

▶︎ Conversely, there are concerns that new technologies like AI might take away jobs. What is your view on this?

I believe there are technologies that have unfortunately faded or are currently fading in the past. However, through my research, I do not intend to eliminate what has been inherited. My idea is not to replace traditional technology with new technology, but rather to use it in areas where Kigumi has not been utilized before, adding new value to products. The vision is to create a different path separate from traditional Kigumi, allowing Kigumi itself to endure long into the future amid changes in people’s skills and lifestyles.

▶︎ I think you truly embody the concept of Onkochishin (Japanese word meaning : Learning from the past to gain new knowledge and insights). Harmonious coexistence, rather than replacement, is the key to progress for traditional technologies.

Developing new technologies and materials to achieve progress is necessary, so I am not saying “Scrap and Build” is inherently bad. However, things made with new technology often encounter various problems later on, such as ending up being expensive, lacking sufficient strength, or being harmful. In this way, if we only pursue novelty or cutting-edge technology, it might end up being just a temporary trend.

I believe that by considering why ancient techniques remain with us today and applying them, they continue to exist as an indispensable part of a country’s culture.

▶︎ If the system can be used by everyone, from children to the elderly, new sensibilities might emerge, potentially creating various new things/values.

I am part of the User Interface Research Lab that conducts research in Computer Graphics and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). While my interest led me to apply this to wood, By applying 3D modeling to real materials like wood, we can achieve things that were previously difficult for computers to handle. This, in turn, can spark entirely new ideas.

I am also interested in Nishijin-ori weaving from Kyoto; I believe that by utilizing CG, anyone might be able to weave, making the technology easier to inherit. Thinking this way, doesn’t it make you all more interested in craftsmanship/making things?

However, I do not envision a future where machines automatically do everything at the push of a button. The final steps of assembly and completion are enjoyable, and I believe they should remain in human hands.

Diverse Challenges for a Sustainable Society

▶︎ I heard that Tsugite is a part of the larger Re:wood Project. What other research is included in the Re:wood Project?

Tree branches are maintained to shape them or cut the side branches to ensure the main trunk grows straight and thick. However, the cut branches have low utility value and are mostly disposed of by burning or other means. That’s why we created “Branch”. This is a software that scans individual branches, each with a unique shape, imports the data into a computer, and allows for various designs to be created by combining this data. Its feature is the ability to create added value and reuse the branches—which were originally discarded—by transforming them into different products while keeping their original shape.

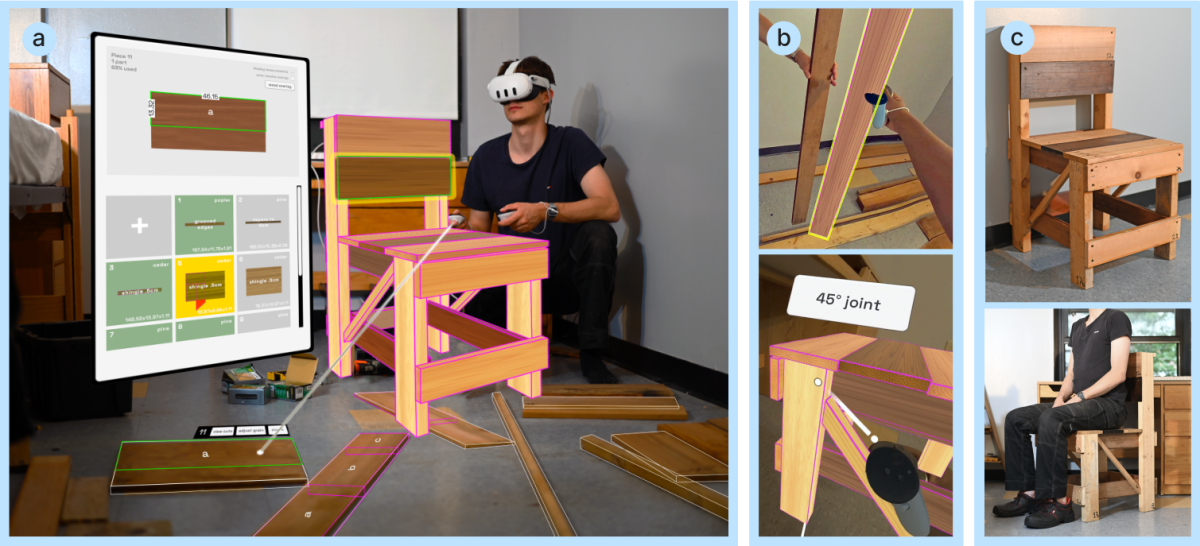

“XR-penter” is another project on discarded wood, but this time focusing on rectilinear wood cut-offs of various dimensions. We developed an extended reality (XR) application for modeling structures with such scraps.

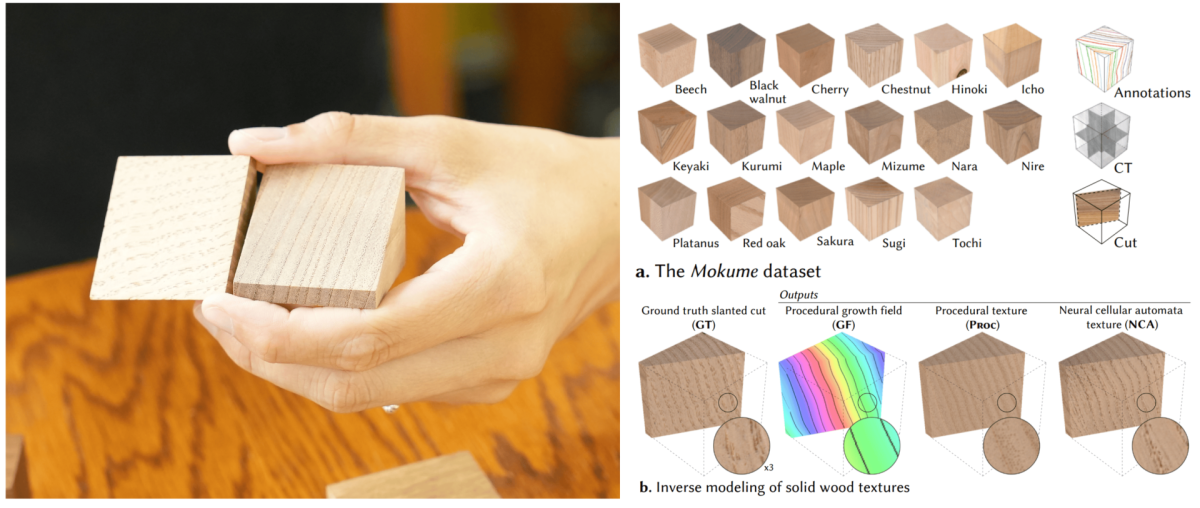

“Mokume” is a software that predicts the internal wood grain structure from a photo of the wood’s surface. Predicting the internal grain makes it easier to select usable parts when combining wood or using it as a raw material.

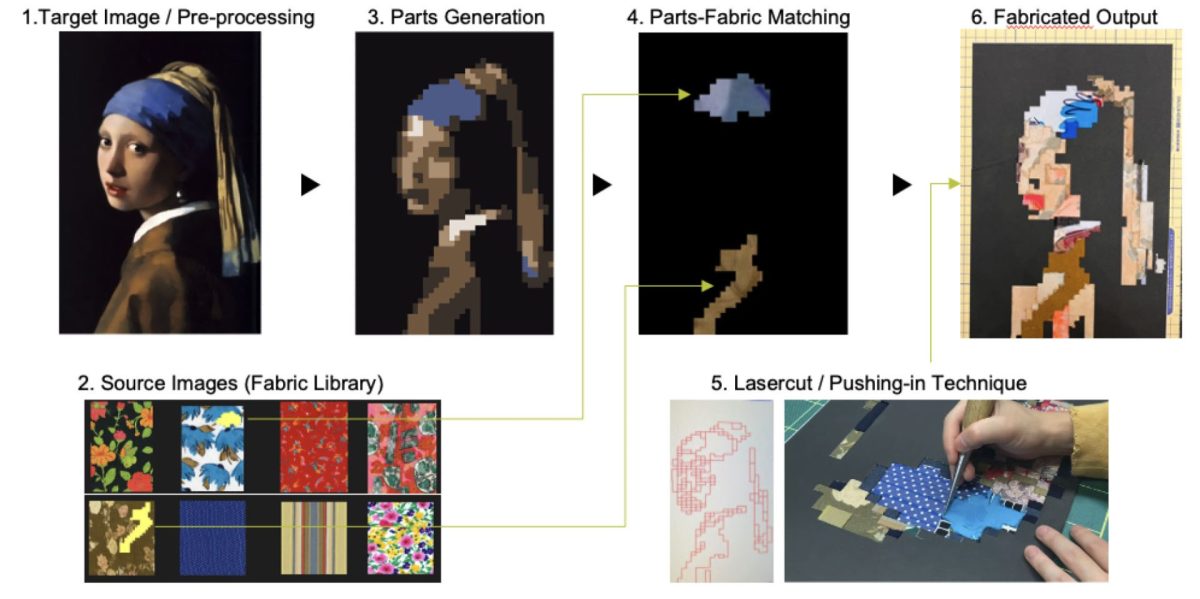

Outside of wood, we also developed a series of projects for upcycling fabric scraps. Fabric Mosaic Art is one of them.

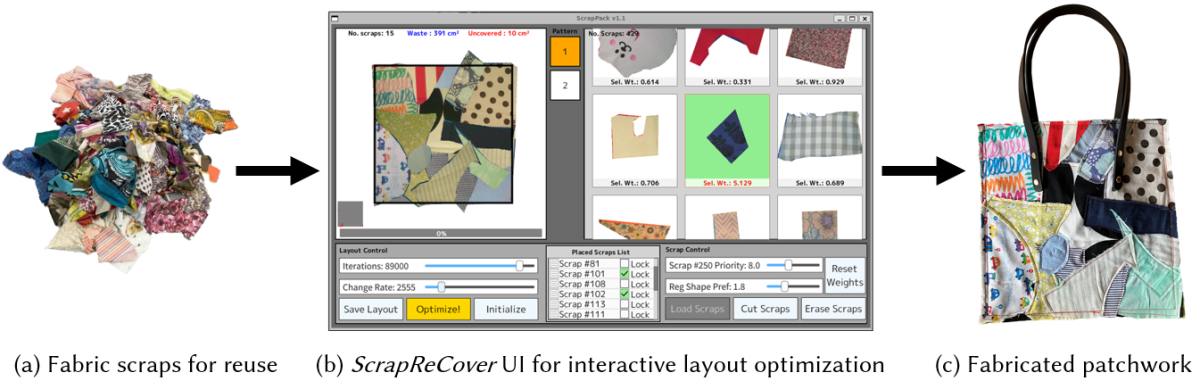

We also created an interface for designing patchworks from scrap fabrics, where a software helps the user to design a layout such that the randomly shaped pieces fit together like a puzzle.

▶︎ Your research reminds me of the traditional Japanese culture, which may have changed over time, where it was common to repair and reuse items rather than discarding them.

For example, Kintsugi (mending broken ceramics and covering them with gold) does not simply repair but it adds unique value, reviving it to be more beautiful than the original. Similarly, I believe that a society that enables people to use things longer by repairing or replacing necessary parts is better than one defined by mass production, mass consumption, and mass disposal.

Rewoodイメージ-1200x675.png)

▶︎ If the applications you’ve developed were to become commonplace and wood was widely recognized as a circular material, what would society and people’s lives look like?

By extending the product lifecycle, people’s mindset and values towards things will likely change, leading to a culture of cherishing objects and repairing only the broken parts to continue using them. A society where metal and plastic products are replaced by 100% wood products using kigumi may become one that reduces the amount of waste and places less burden on the planet, society, and people.

Beyond Kigumi, a society where cherished traditional techniques coexist with latest technology will inspire people’s imagination. I wish for a society rich in creativity, where individuals feel empowered to pursue what they want to create and achieve.

▶︎ Her research seems achievable because she possess the combined cultural values of Sweden and Japan, both of which have a close relationship with wood and nature. Her attitude of learning from tradition, gaining new knowledge and insights for the future, and putting it into practice truly embodies Onkochishin. I recently heard news of a wooden satellite being built. The value of wood now extends to space, suggesting infinite possibilities, which I find astonishing. I look forward to being continually excited by your research. Thank you for this wonderful time.

Value Exchange Engineering PR, Kawanaka

Related Link

・Maria Larsson

・Tsugite – Full video – UIST 2020

・https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mHKNnDBAkDU